by Ken Dobb

History has been less kind to the memory of Pierre Giffard, the great rival of Henri Desgrange. Remembered by cyclists chiefly as the founder and first organiser of Paris-Brest-Paris, his role in sports history was somewhat wider and, in his own way, he was no less a significant figure than Desgrange.

Giffard was, above all, a journalist. He worked for a French press that closely mirrored the social divisions of the late-nineteenth century. Newspapers of the era were linked directly with political groupings: competition was not simply a matter of commercial success, but, as importantly, a way of building political influence. By the 1890's, already a veteran of over twenty years of journalistic experience, he was employed by the Parisian newspaper Le Petit Journal as chief correspondent. It was an era which saw the emergence for the first time of organised sporting activities in France, not the least of which was cycling.

Cycling: Paris - Brest - Paris

The emergence of cycling resulted directly from a revolution in cycling technology in the 1880's - principally the advent of the safety bicycle. The application in 1885 of the chain and cog mechanism to transfer propulsive energy to the rear wheel, led to a fundamental change in frame geometry: from the perilous high wheeler to the "safer" configuration of the small-wheeled diamond frame. This innovation was followed rapidly by other improvements to spokes, wheel rims, brakes and, importantly, pneumatic tires. By the end of the 1880's, something closely approximating the modern bicycle had come into being. Its promoters sought venues in which to display its worth.

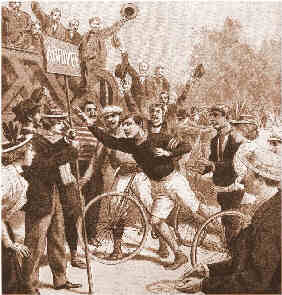

The first such venue to catch the attention of the French public was a race jointly announced in 1890 by the Velo Club Bordelais and the leading cycling periodical of the day, Veloce-Sport. Bordeaux-Paris was held on May 23 -24, 1891 on a 572 kilometer route. It was the first inter-city race to feature the safety bicycle. A crowd of 7000 were on hand in the Port Maillot, near the northern corner of the Bois de Boulogne, the site in Paris of the Velodrome Buffalo, to meet the cyclists as they arrived at the race finish.

Le Petit Journal, noting the spike in its circulation its coverage of the event had caused, charged Giffard with organising a more challenging event that would sustain the interest of its readership over a longer period. And so, several months later, the first Paris-Brest-Paris was held. It was to be the first of several events organised on behalf of the newspaper by Giffard. The next significant undertaking, however, was not a cycling event but a mass participation event that combined cross-country running with hiking.

Athletics: Paris - Belfort and the Paris Marathon

As was the case with cycling, athletics, and particularly running, emerged as a sport in the last decade of the nineteenth century. In 1889, the first national organisation was formed, grouping together French athletics associations. Athletics were promoted by the first periodical devoted exclusively to the sport - La Revue Athletique. This was a monthly publication started in 1890 by Pierre de Coubertin, who would later found the modern Olympic movement. Coubertin was an important proponent of amateurism in sport. He emphasised the virtue of participation in sport for its own sake, downplaying the competitve aspect and the emphasis on winning inherent in sporting activities. These ideals found their way into the organisation of sports activities other than running.

Runners remember Giffard as the organiser of Paris-Belfort, a foot race over a course of some 380 kilometers in early June 1892, and the first large scale long distance foot race on record. Over 1100 registered for the event of which over 800 showed up for the start on June 5th, at the offices of le Petit Journal, close to the Paris Opera. This had also been the start point for the inaugural Paris-Brest-Paris the previous year. Again, circulation of the newspaper showed a dramatic increase as the French public followed the progress of race participants, 380 of whom completed the course in under 10 days. Giffard waxed eloquent in a summation of the event in the pages of le Petit Journal on June 18th, 1892, praising the event as a model for the physical training of a nation faced by hostile neighbours.

Giffard returned memorably to the field of athletics in 1896 with the inaugural Paris marathon on July 18, 1896. Although by now editor of his own daily newspaper, Le Velo, he organised the event on behalf of le Petit Journal, an arrangement that suggests a continuing relationship between the two publications. The marathon was held in emulation of the inclusion, at the insistence of the Greeks, of the event in the inaugural Olympics held in Athens earlier that year. It was Giffard who started the race before a large crowd assembled at the Port Maillot. The race was won by an Englishman, Len Hurst, who collected the 200 franc prize money put up by Le Petit Journal. This was to be the last marathon held in Paris until the mid-1980's.

As a final hurrah, Giffard organised a footrace on the Bordeaux - Paris race route in 1903. This race was won in the time of 114 hours, 22 minutes and 20 seconds. But, by this time, his rivals had undermined his competitve position. Le Velo was within months of collapse.

Automobile Racing: Paris - Rouen

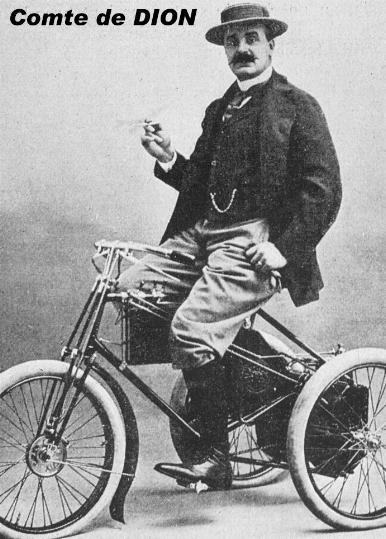

Equally, Giffard was the first to organise a significant event in the field of automobile racing. Like bicycles, with which they share a common early technological history, automobiles emerged in the last decades of the 19th century. Among the first to enter the field in France was the Marquis Albert de Dion who had become interested in a small steam engine built by a Parisian artisan, Georges Bouton. By 1887, the firm of De Dion Bouton had managed to produce several prototype steam tricycles. Although other firms had begun to enter the field, in the first French automobile race organised by Velocipede magazine in 1887, Georges Bouton was the winner and only participant.

If the timing of an automobile race in 1887 was premature, by 1894 the timing was ripe for a showcase event. Giffard, who had permitted an automobile to participate in the inaugural Paris-Brest-Paris (the automobile's average speed on the course 14.7 kph: Charles Terront's average speed, 16.9 kph), was asked to organise the event. There was hope that the race could generate the same sort of favourable publicity for the automobile that Paris-Brest-Paris had earned for the safety bicycle.

The course chosen was Paris - Rouen. One hundred and two competitors registered for race, the entries featuring an assortment of power sources bewildering in its variety (including one human-powered pedal vehicle). Of those, who actually started the race, 25 remained in the field at the 50 kilometer mark. The finish line was crossed first by a steam tricycle entered by De Dion Bouton, with an average speed of 20 kilometers per hour. However, the Giffard-selected race jury adjudged the tricycle to be unsafe and uneconomical. They consequently awarded first place, and the award money, jointly to the entrants of the firms Peugeot and Panhard & Levassot. Giffard was to organise a second automobile race in that year on the route of Paris-Brest-Paris, but the event was not well attended, and is scantily reported in history.

The Marquis De Dion, undoubtedly smarting from his disqualification, undertook to organise his own automobile race. In June of 1895, the inaugural Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race was held over a course of 1175 kilometers. Ironically, the race was won by a vehicle constructed by Panhard & Levassot, with a Peugeot-built automobile in second place. To deepen the irony, the firm of De Dion Bouton came to abandon the steam engine, on which the fortunes of the firm had been built, in the first years of the next decade.

But it was too late for Giffard. Later in 1895, De Dion, with the assistance of other automobile industrialists, founded the Automobile Club de France. This grouping was charged with the organisation of automobile races in France, and further, with the defence of the industry against public initiatives to limit the growth of what was still widely perceived to be a dangerous vehicle. The responsibility for this latter undertaking was placed in the hands of another journalist. Giffard had been effectively cut out.

Le Velo

Giffard's newspaper, Le Velo, was launched in 1892 with a particular advantage in the late-nineteenth century market for sports publications. It was published as a daily newspaper. Its publishing schedule soon allowed it to displace its two chief rivals - La Bicyclette and Veloce-Sport both published weekly. Printed on green paper, by mid-century it had reached a daily circulation of 80,000 and had attained a dominant position in its market. La Bicyclette responded by purchasing in 1894 a small daily called Paris-Velo that had been created in 1893. This paper was printed on pink paper but was to prove only marginally successful. More significantly, the success of Le Velo drove Veloce-Sport, one of the prime movers of the first Bordeaux - Paris bicycle race, out of business. With the failure of this rival, Giffard was able to assume sponsorship of the event.

By the last decade of the nineteenth century, cycling had become the dominant sporting event in France. Giffard consolidated his grip on his market by assuming sponsorship and promotion for a sizeable number of races across the country. Many of the races of this era - Paris - Besancon, Lyon - Paris - Lyon, Rennes - Brest, Paris - Tours - are no longer remembered. This is not the case, however, of Paris - Roubaix, a race that was created in this era and which has become the most famous of the Spring Classics. This race, first held on April 19, 1896, was the product of the research, and some miserable early season cycling, of a young journalist in the office of Paris-Velo, a sometime colleague of Henri Desgrange, named Victor Breyer.

It was quite possibly his control of Bordeaux - Paris that persuaded Giffard to give up the organisation of Paris - Brest - Paris. Regarded unfavourably by cycling professionals who resented the training the exceptional distance of the race required, participation by racers was expected to be low. Race organisation fell to Henri Desgrange, recently appointed director of the new rival publication L'Auto - Velo. It was Desgrange who, in the second edition of the event in 1901, opened up the event to non-professional sport tourist cyclists - this decision three years before he was to organise the French branch of Audax cycling.

By striking successfully at Bordeaux - Paris, first by running an alternative edition of the event in 1902, and then by creating the event - the Tour de France - that was supersede Bordeaux - Paris in the imagination of the French public, Desgrange was aiming at the heart of Giffard's enterprise. Desgrange was by training a lawyer. However, he was overtaken by a passion for cycling and earned his living, while pursuing his cycling career, as a part-time correspondent for La Bicyclette. This would make him a contemporary of Pierre de Coubertin in sports journalism. Indeed de Coubertin was still an active member of the association of Parisian journalists at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Through time, Desgrange came to work in public relations for Adolphe Clement, head of Cycles Clement, the largest bicycle manufacturer of the era.

It was Clement that brought forward Desgrange's name to direct L'Auto-Velo, the daily newspaper founded by a group of industrialists disgruntled with the stranglehold exerted by Giffard on sports journalism. This group, that included the Marquis De Dion, Baron de Zuylen - the head of the Automobile Club of France, Edouard Michelin, as well as Adolph Clement, had a variety of interests to advance They were concerned with the promotion of their own events, cheap access to an advertising source for their products, as well as, probably, a common political agenda.

The introduction of L'Auto - Velo in October 1900 was the beginning of the end for Giffard. Circulation of the new publication ate into that of its senior rival. Circulation spiked after the success of the alternate edition of Paris - Bordeaux, only to have the circulation of the paper printed on yellow newsprint fall back to 20, 000 in the aftermath of Giffard's last gambit, a legal suit to change the name of the rival publication.

The success of the Tour de France spelled the death knell of Le Velo. The last edition was published in November 1904. With it, Pierre Giffard - the dominant sports promoter of his era - slipped into obscurity.

For his part Desgrange never forgot the lessons of these early newspaper wars. When, in 1920, members of the Parisian branch of the organisation of Audax cyclists he had helped to create, assisted in preparations for a race sponsored by a rival newspaper, Desgrange expelled them. He forbade them to organise events under the rules of French Audax cycling. This was the beginning of the fundamental schism in sport tourist cycling that has resulted three-quarters of a century later in the affiliation of clubs from around the world with Audax Club Parisien.

Copyright 2025, Randonneurs Ontario

Comments? E-mail the WebMaster